A Year Late and a Dollar Short: 2007 in Review

Most fashionable Romanian women try to dress like their beverage bottles.

As of January 2009, I still have not seen all the movies from 2007 that I wanted to see. This is the blessing and the curse of being a cinephile in an age when technology has allowed my favorite medium to proliferate: I will never want for new, intriguing cinema; I will also never be able to catch up. The best I can do is slog ahead, basing the priority ranking of my Netflix queue on the recommendations of friends and reliable critics, or the odd trailer or synopsis that happens to stir interest. As terrible as many of the films were in 2007, the great moments more than made up for the mediocre and flat-out abysmal failures that littered the multiplex and direct-to-DVD outlets.

Forget the Money — I Want My Time Back!

I see many movies I shouldn’t. I’ve been watching movies long enough to know from a preview or the critical consensus which flicks are likely to align with my taste, yet I go to see the sure-failures anyway. This is how I wind up bitching about crap like Fantastic 4: Rise of the Silver Surfer, Hitman, and Shoot ‘Em Up, though the most reasonable response to such spleen venting is, “Dude, what did you expect?” Some of these are truly wretched films, but the worst offenders are the ones that, by pedigree, ambition, or perhaps a single, fatal flaw amidst mostly worthy filmmaking, fall so far short I wind up mildly offended (by myself, partly) that I trusted them in the first place. Here’s a small sampling of the worst of the worst offenders.

5. Smokin’ Aces (d. Joe Carnahan). Oh Lord, Oh Lord, what hath Tarantino wrought? Hopefully this wretched, hypocritical thriller represents the tail end of the “I Wanna Be QT!” wave that followed in the wake of Reservoir Dogs and Pulp Fiction. Carnahan treats his characters with brutal contempt or maliciously ironic humor, indulging a dozen scenes of mock-philosophical tough talk, climaxing in a gleefully exploitative bloodbath, before ending on a note of righteous anger outrageously out of step with the tone of the rest of the story. If this isn’t the nail in the coffin of hipster crime movies, I hope it is at least the tolling bell for which I desperately pray.

4. Aliens vs. Predator: Requiem (d. Colin Strause, Greg Strause). Of all the crappy SF/fantasy/horror/action films I saw, this one stands as the worst of 2007. On its own terms, it is incompetent, sloppy, and foul. As the latest entry of two series that used to have mainstream respect, it is an abomination. Finally the filmmakers have capitulated to the lowest common denominator, abandoning all ambition to elevate genre trappings to something more viscerally meaningful or thematically interesting, and turning the Alien/Predator franchise into a bargain-basement slasher flick.

3. Atonement (d. Joe Wright). I hated the ending. I didn’t mind that it was tragic. I like tragic tales, done right. I minded that it was played as “Gotcha!” joke on the viewer that added nothing thematically to the story. If Verbal Kint adapted Ernest Hemingway, it might look something like this, but I’ve already seen The Usual Suspects and A Farewell to Arms, thank you very much. Leave the twist endings to M. Night Shyamalan, Christopher Hampton — write the movie, not the movie-of-the-book. The worst part is that Joe Wright displayed a command of cinematic language with which Shyamalan has yet to flirt. We expect this kind of crap from him. Don’t set your sights so low, Joe.

2. Across the Universe (d. Julie Taymor). Aside from the surprisingly adept re-contextualization of “Strawberry Fields Forever,” Julie Taymor has fallen prey to the kind of 60s idolatry unseen in English-language filmmaker since Oliver Stone made wild monkey love to the decade through his avatar, Jim Morrison, in The Doors. Rendering Beatles tunes with idiotically literal translations, Across the Universe is devoid of the anarchic momentum of the Fab Four’s Richard Lester comedies or the grandeur of their more visionary compositions. After forty years, someone has finally made Beatles Anthology: The Musical!, and accomplished the near-impossible task of cheapening the most iconic music of the 60s, and entrenching it so firmly in the past that it is now completely irrelevant. Thanks, Julie.

In the Rogen/Apatow universe, the pickup line that works for fellas like this is: "Hey, babe. If you pass out, can I stick my dick in your ass?" Works every time.

1. Superbad (d. Greg Mottola). A pair of stupid teenage boys embark upon a quest for alcohol, so that they can get a couple of hot girls drunk and screw them, because it’s cute and sweet to get girls liquored up and fuck them when they’re too inebriated to know what they’re doing. But wait! It’s actually a movie about friendship! And cartoon penis drawings! And Jonah Hill’s inability to say a complete sentence without the words “pussy” or “fuck!” How could I not relate to this movie? Oh, that’s right: because I respect women to much to aspire to date rape, and because I like my comedies to be clever, interesting, and, you know, funny. Superbad is none of those things. It’s the most reprehensible piece of garbage to come out of Hollywood in 2007, and its profitability only reinforces my gratitude that I’m apparently out of touch with what the people want.1

I Laughed, I Cried, I Made a Top Ten List

As usual, it seemed that most of the best movies of the year became available to me in the last four months when they finally hit DVD. I’d say there were 20 extremely good to arguably great films released in ’07, but I narrowed it down to ten, because I enjoy being arbitrary and privileging my own subjective taste in the form of an objective ranking. Elitism tastes yummy! Included with a few of these entries are “honorable mentions” that I thought tied in thematically with my selections. Perhaps you can use them as an inspiration for a double feature.

10. Ratatouille (d. Brad Bird). No film in 2007 better articulated the relationship between consumers, artists, and critics, than this delectable fable. Like any film in which the preparation of food adopts a spiritual aspect (Babette’s Feast and Como agua para chocolate spring to mind), Ratatouille plants one foot in populist digestibility and the other in artsy, ephemeral allegory. Animation remains one of the most cinematic forms of film narrative, and its far-out premise is made all the more immediate and real by the warmth of the voice work, the detail packed into the frames, and the feeling that this is the purest of platonic forms, even when engaged in ribaldry and postmodern wordplay.

Like any self-respecting hipster, Cate taps her cigarette ash into thin air and blows it away with a vacuous stare.

9. I’m Not There (d. Todd Haynes). I’m actually a bit surprised to find this title on my list. But as I thought and wrote about it in preparation for this article, I realized that one of the most cinematic movies of the year was Haynes’s collage of 60s and early 70s iconography, all swirling around the “lives and music of Bob Dylan.” Haynes also goes for the throat, but his subject is too obtuse and too instantly recognizable for him to gain any traction. Like a feature-length music video, I’m Not There is gorgeous, hypnotic, and enchantingly realized; it says nothing, of course. Making inroads to the psyche of Bob Dylan is the quest of a fool, and Haynes is no fool. He plays with the free associations anyone passingly (as I am) familiar with the former (erstwhile? Late? Immortal?) Robert Zimmerman, commenting on the absurdity of each association’s apparent earnestness, and the absurdity of how seriously we take it. As a lark, a multi-level pastiche of capital-C Characters and settings from another time and place (so very much unlike our own!), it’s a wonderful trip down a memory lane you needn’t have lived through. In a way, it’s the year’s diametric opposition to Across the Universe. A gonzo family album full of flattering (and unflattering) poses, I’m Not There is a complement to Dylan’s music, not an exegesis of the man. Its very lack of ambition is a halfway-there achievement; mostly I just liked having all those talented actors and all that great music in one place.

8. The King of Kong: A Fistful of Quarters (d. Seth Gordon). Not innovative or challenging in any way, the best documentary of the year was a simple David and Goliath grudge match between a couple of grown men obsessed with an 80s arcade game. The lengths to which these all-American guys go to be the best at something is marvelous: hope in the face of adversity is now synonymous with a fat plumber fighting a giant ape with an endless supply of barrels. Genius. Honorable mention: There Will Be Blood (d. Paul Thomas Anderson). King of Kong’s obvious corollary is epic saga of macho one-upsmanship set against the backdrop of religious fundamentalism and oil profiteering at the dawn of the 20th century. Anderson’s real satire is directed at alpha male dominance; the theatrics of Daniel Day-Lewis and Paul Dano’s crippled avatars are just as pathetic as they would be in a 21st century milieu, but the virgin territory of the American West and the retrospective lens of time grants them a more mythic status than they’d perhaps acquire in the corporate boardroom or mega-church televangelist pulpit. In the end, both films are about American men for whom no sandbox is big enough to share. One wants the other’s pail, whether it holds quarters or a milkshake.

"Oh no! A Mod Squad marathon! Why!?!"

7. Stardust (d. Matthew Vaughn). Fairy tales are tough to translate to the screen in the 21st century, with outmoded tropes and attitudes that must be filtered through the lens of postmodern criticism to be acceptable. Precariously balanced between these two realms of awareness is the imagination of Neil Gaiman, obsessed with the transcendent possibilities of “Story,” in all its forms. Vaughn doesn’t achieve transcendence, but Stardust is rollicking, old-fashioned, and diverting — a hero’s tale that equates romance and adventure, along with all the lumps and bruises acquired along the way. It never aims for the kind of cinematic realism Peter Jackson strove to create with his CGI-enhanced Tolkein adaptation, but Gaiman has never been overly concerned with realism, so long as the stories are Real Stories. Stardust is a Real Story robed in the glamour of a fairy tale.

6. The Bourne Ultimatum (d. Paul Greengrass). Though it now appears that this was not the end of the Bourne trilogy, Ultimatum does bring the Bourne movies full circle: Jason Bourne learns who he is and who he was, and the vast difference a little experience can make. Not quite on par with Supremacy, Ultimatum is more ambitious and daring, and when it finally places moral responsibility on the soldier as well as the men who give the orders, the payoff is liberating. “Do you even know why you’re supposed to kill me?” In Identity, Bourne had no idea who was trying to kill him or why, and now that he knows how dangerous he is (and how well he perhaps deserves punishment), his greatest triumph is instilling that thirst for self-knowledge in those chasing him. Essentially, he has felled his enemies with human curiosity, a lesson taught without the least hint of didacticism. Plus several awesome suspense sequences to boot!

5. Hannah Takes the Stairs (d. Joe Swanberg). I can only surmise that the title is an allusion to the title character’s predilection for doing things the hard way every time; perhaps also an allusion to her climbing her way to equilibrium on the backs of well-meaning, but ill-suited suitors with whom she shares intense, but brief affairs. Swanberg has come a long way from his “unflinching” sex drama Kissing on the Mouth; perhaps discontent with being an affable, but inoffensive faux-vocateur, the Chicago-based (and Detroit native) filmmaker has finally embraced a navel-gazing, egalitarian fascination with his comrades-in-DIY-arms that lets his characters breathe, his actors be themselves, and his artistic vision be guided by the nuances of rhythm and emotion suggested by the events onscreen, more than his thematic ambition (which took over Kissing on the Mouth and LOL, which was good, but a bit too schematic). More than that, it showcases Greta Gerwig as the minor-key star she was born to be. As vexing as she is — as both a screen presence and character — she is the most propulsive element in the film, a commanding narcissist unable to articulate just what the hell makes her so engaging, neurotic, or worthwhile. This compulsive dissembling is an art unto itself. Honorable mention: Quiet City (d. Aaron Katz). Even amongst the so-called “mumblecore” films (as vague a grouping as any nouvelle vague can be), the constant chatter and anxious camerawork barely lets the characters just exist. Aaron Katz seems to have found a way to counteract this tendency. His Quiet City protagonists, Jamie and Charlie, are so appealingly ordinary, that Katz is content to simply record what happens. In the absence of narrative, story prevails, and nothing is more simple or more beautiful than the natural blossoming of love.

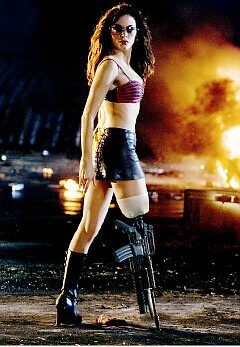

4. Grindhouse (d. Robert Rodriguez, Quentin Tarantino, et al.). An extended in-joke for hardcore genre aficionados, the Grindhouse project may have failed to be more than a sum of its parts, but with directors like Rodriguez, Tarantino, and Edgar Wright pitching gummy love notes (sticky and swollen with pass-it-on smooches) against a wall to see what sticks, the cumulative impact of the parts is intense — even if they add up to nothing beyond a confectionary indulgence on the part of the filmmakers. Of all of them, Rodriguez makes his delight the most apparent. His home-movie approach to the craft is perfectly suited to the lowbrow wallop packed by Rose McGowan’s mind-blowing prosthetic assault, uh, leg. Honorable mention: Hot Fuzz (d. Edgar Wright). Grindhouse’s fake Don’t trailer creator Wright’s sublime buddy comedy had the stated intention of parodying American action films and British countryside mysteries, but the bizarre alchemical process by which Wright and cowriter/star Simon Pegg distill their ideas resulted in an absurd masterwork that stands as an homage to small-town life, persistence, friendship, the acceptance of homoeroticism, and the art of blowing shit up awesomely. It’s sophisticated and crude, taking the piss out of genre and art film snobs alike, floating the notion that perhaps stupid action comedies function as an inspiration for community engagement and male bonding. Also, gouts of CGI blood. Cool.

3. 4 Months, 3 Weeks, and 2 Days (d. Cristian Mungiu). Like the Coen brothers’ No Country for Old Men, this Romanian critical fave is an extension of noir conventions, filtered through the lens of realist drama, just as No Country was filtered through the cinematic landscape of the Western. Most critics took 4, 3, 2 as a (perhaps problematic) abortion rights parable. It works on that level, but just as the first movies identified as films noir weren’t patterned after a particular style or genre theme, but grouped together by critical consensus, I think the longevity of Mungiu’s film will depend on the elasticity of his ethical perspective and the finely-tuned layering of his deceptively steady gaze. Unlike Tony Kaye’s abortion doc, Lake of Fire, Mungiu doesn’t confuse the indulgence of various perspectives with the clarity of moral nuance. The profound ambivalence of the characters toward the larger political climate isn’t reflective of his lack of engagement so much as a tacit admission of the incomprehensibility of the moral quagmire overwhelming western civilization, and the unthinkable violence that pervades it.

Bowflex v. 2.0.

2. The Mist (d. Frank Darabont). Confronting the most terrifying question of theology — not whether or not God exists, but whether or not he’s a cruel, capricious son of a bitch — this Stephen King adaptation contains many familiar King pitfalls (lack of a strong female protagonist, characterizing religious folk as insane zealots). Darabont compensates brilliantly with a visceral approach, utilizing roving (yet precise) camera movements, tense introspective moments, amazing soundscapes, and the best use of Lovecraftian creatures in years. Every element falls neatly into place, and Darabont has the grace to not overextend his resources, financially (by dumping tons of cash into CGI set pieces) or temporally (by keeping the pacing tight and the running time taut). Darabont engages human relationships on the family, community, ideological, and existential level without ever resorting to impertinent sermonizing. It’s a carefully-observed microcosm that could very well be The Ox-Bow Incident or The Crucible as written by Lovecraft and designed by Francis Bacon.

1. The Assassination of Jesse James by the Coward Robert Ford (d. Andrew Dominik). A little too long to gain traction in box office receipts, and kindly-but-unenthusiastically received by the critical consensus, Robert Ford is one of the most potent portraits of outlaw life I’ve ever seen (historical accuracy be damned!), and boasts what ought to be a career-making performance by Casey Affleck. For a film that runs nearly three hours, and features scant few violent interludes to break up the visually-stunning tableaux, the time flies by. Read my extended commentary here.

Edited by Ellen Lawrence and Tracy McCusker.

An age-old debate: crane versus viper. One will emerge victorious. One will have to make the peanut butter sandwich.

____________________________________________

- The great tragedy of the film is that McLovin was a pretty good character, and the laughs I got were from his storyline. ↩

Leave your response!